Life did not stop in Livingston when the government removed its status as the county seat. Two lawyers were traveling on horseback from Cassville, the county seat of Cass County, on their way to court at Livingston, the county seat of Floyd. The lawyers, a day early for court, stopped at a small spring separating the Etowah and Oostanaula Rivers.

It was a warm spring day in 1834. Sitting under a shade tree, the two men admired the surrounding hills and had this conversation: “This would make a splendid site for a town,” said Colonel Zachariah Hargrove. “I was thinking the same,” said his fellow lawyer, Colonel Daniel R. Mitchell. “There seems to be plenty of water round about and extremely fertile soil and all the timber a man could want.” (Battey, 1922) A stranger overheard the conversation and introduced himself as Major Philip Walker Hemphill. He apologized, “Gentlemen, you will pardon me for intruding, but I have been convinced for some time that the location of this place offers exceptional opportunities for building a city that would become the largest and most prosperous in Cherokee, Georgia. I live two miles south of here. . . I never pass this spot but I think of what could be done” (Battey, 1922). Hemphill invited the lawyers to spend the night in his home.

After court in Livingston, they returned to Hemphill���ӽ紫ý home to discuss plans to build a new city 14 miles above Livingston. Col. William Smith was called in from Cave Spring to round out the company. They talked of acquiring the ferry rights to the rivers and laying out the land by lots. Finally, they talked about drawing up a bill for removal of the Native Americans still on the land. A fifth member of the party joined in. John H. Lumpkin was a lawyer who served as a secretary to his uncle, Governor Wilson Lumpkin. Lumpkin would deal with the legal issues, as Mitchel and Hargrove had established law practices elsewhere.

The five men put their choice of town names into a hat. Colonel Mitchell remembered visiting Rome, Italy, and the beautiful seven hills. It reminded him of this place in Floyd County. He put “Rome” on a slip of paper and into the hat. They chose that name (Battey, 1922). This marked the beginning of the end of Livingston as the county seat and, eventually, as a Floyd County town.

Livingston was originally called Mission Station, because the white man brought missionaries to “civilize” the Cherokees. Long before this, in the sixteenth century, Hernando de Soto may have visited the area in search of Southern gold. De Soto or Tristan de Luna y Arellano left evidence on the McGee Bend on the Coosa River.

In 1830s Georgia, the white man had an insatiable hunger for land. Although the federal government had promised to deal with the “Indian problem,” Georgia was impatient. The government divided the Cherokee Nation into 10 counties. Gold discoveries in North Georgia prompted the state legislature to redraw its boundaries across much of the region. It created counties and a series of rules that restricted Native Americans on their own property.

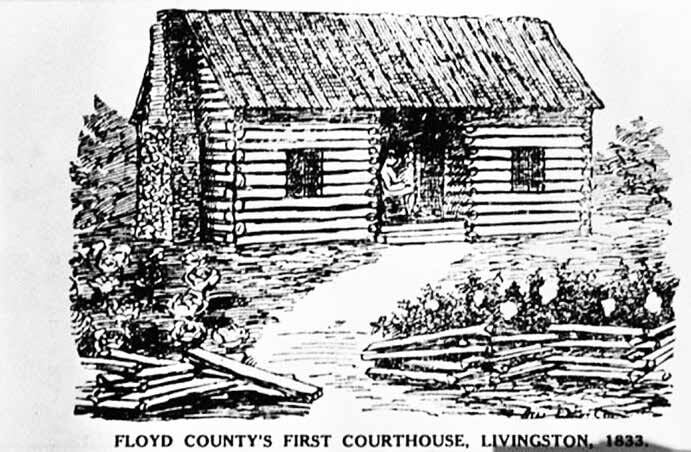

After being surveyed by Jacob M. Scudder, a ���ӽ紫ý government official, Floyd County was established. The county was named after General John Floyd of Camden County, a noted Indian fighter. On December 21, 1833, Livingston was named the county seat. According to the Rome-News Tribune, “The county seat was placed at Livingston, now a crossroads where Foster���ӽ紫ý Mill Road and Morton Bend Road meet, but then a bustling pioneer settlement. At the time, Rome did not exist.”

Many cases were brought to the tiny log cabin courthouse, with Judge Hooper presiding. Native Americans were both defendants and prosecutors in this primitive court. Hooper was often criticized for being fair with the Cherokees. Livingston was the government seat for two short years.

What Hargrove, Mitchell, Hemphill, Smith and Lumpkin discussed in spring 1834 was set in motion, and the legislative act passed on December 20, 1834, moving the county seat from Livingston to the new town, Rome. The year 1835 marked the successful completion of this endeavor. These lawyers, businessmen and well-connected politicians moved fast to grow Rome.

Livingston United Methodist Church remains to this day but is stands vacant surrounded by a fascinating graveyard that some say is haunted, but that is another story. While the Methodists stayed, the First Presbyterian of Livingston moved to Rome in 1845. Jackson Trout had built the first wooden home in Livingston. He put the structure on skids, loaded it onto a barge and pulled it to Rome on the Coosa River. Others did the same, but many got stuck when they reached Hors Leg Shoals.

At this time, Rome was a virgin forest. People would just put up a tent and stay as long as they wished. The Cherokees stayed in Rome in tents, waiting for word of their removal. The remaining Cherokees were still a problem.

In his history of Floyd County, George Battey mentioned a report from Capt. J.P. Sim, disbursing agent of the Cherokee Removal in September 1837. C. Hardin was president of the Western Bank of Georgia, of Rome. Col. Hardin and Andrew Miller, agent of the Bank of Georgia, of Augusta, loaned the Government $25,000. Funds were transmitted through the Rome bank toward the removal of the Cherokees. Once the Indians were gone, Rome and Floyd County experienced remarkable growth. Livingston did not.

Life did not stop in Livingston when the government removed its status as the county seat. It was a sociable and active community well into the twentieth century (1924). The hamlet had a one-room schoolhouse. The Methodist church, one of the oldest in North Georgia, coordinated activities with the school. They shared fairs and box suppers and worked so closely, no one could tell who sponsored an event. According to the locals, “There was never a lack of things to do when it was town.” Frances Erwin Evans remembers hayrides and picnics. She recalls swimming or wading in the creek and attending ice-cream suppers.

Mrs. Evans said that during World War I, friends would sit around the campfire and sing popular songs, such as “Over There,” “It���ӽ紫ý a Long Way to Tipperary” and “A Rose Grows in No Man���ӽ紫ý Land.”

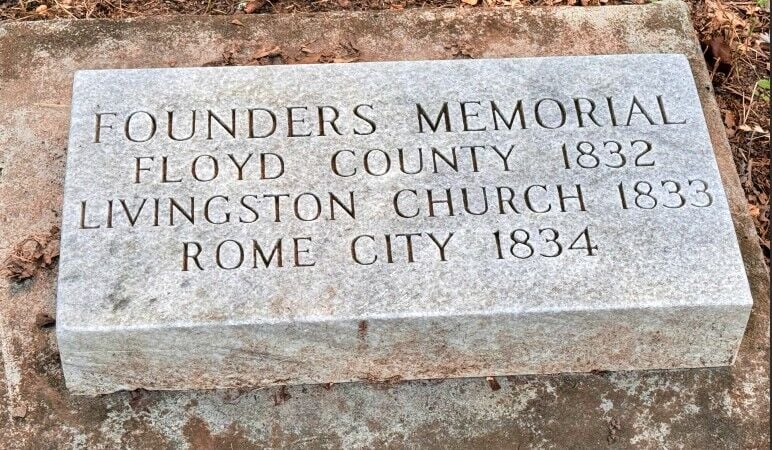

As the 1920s and 1930s progressed, Rome grew, and Livingston became a lonely crossroads. Looking for Livingston is not easy. A small memorial near the UMC Church building tells the story of the founding year of Floyd County, 1832, Livingston 1833, and finally Rome, 1834,. Surrounding that memorial is a stacked stone foundation of either the old church or the old courthouse. Unclear where the old courthouse once stood, Livingston had a very short time to serve its purpose — barely a year.

In its brief life, Livingston heard important court cases in its log courthouse. The school opened children���ӽ紫ý eyes to a wider world. Churches brought salvation and messages of hope. Though Livingston���ӽ紫ý voice is now silent, it speaks in the lives of those who lived there and down the generations.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.